Moving beyond village religion

I'm entirely devoted to the grand and civilisational way of thinking, talking about, and advocating, true subservience to God. By ‘civilizational’ I mean an understanding of true subservience which resonates with the experiences of those who live in an advanced state of human society, as opposed to villages.

As such, for many of us the time for ‘village Islam’ is over.

And yes, the distinction between village Islam (synonymous with desert-dwellers) and civilizational subservience to God has been made in both the Prophet’s time and later on by fuqaha (jurists). There are many hadith that explicitly speak to the distinction, such as, “The testimony of a villager against one from civilised society (urbanite) is not be accepted.” (Abu Dāwūd and Ibn Mājah, and there’s a discussion on its reliability)

Continuing with the distinction, the distinguished Hanbali jurist Mansūr al-Bahūti wrote about leading salah, ‘The urbanite, one who is raised in a city or town, is ranked above the villager, who is raised in a village, because most villagers are crude and have little knowledge of the injunctions pertaining to the rules of prayer. God said of the bedouins, “They are the least likely to know the limits God has sent down to His Messenger” due to their distance from those they may learn from.’

Al-Shāfi’ī provided a nuanced position in his opus Kitāb al-Umm that intimates how he saw it: ‘And if a villager leads an urbanite then it’s not an issue, if God so wills, except that I would like that the people of fadl take the lead in every circumstance of leadership.’ While taking every situation on its own merit, the latter part of his statement suggests that he saw those of fadl (superiority) as tending to be found amongst urbanites.

To be honest, village Islam was never appropriate for us. But economic migration, largely from poor or rural places, meant that it was inescapable. This is certainly not a value-judgement about that generation, but a wakeup call for THIS one. Civilisational subservience to God isn’t just deep knowledge and insight that integrates various fields of learning and enquiry, but it’s also an attitude and a vibe. A culture behind the thinking that becomes the basis of action.

For far too long Muslims have been palmed off with village Islam.

Even when so-called scholars try to present a pseudo-intellectual argument, it's merely village Islam with sources and citations. Village Islam is great for the village and being simple is perfectly fine, but that’s about maintaining a humble status quo that regulates basic impulses by providing simplistic solutions. It is nowhere near erudite or rich enough to provide the tools to build and advance as a community in sophisticated societies, and especially in our western context.

Yet your mosques and institutions socialise you with it, most preachers and teachers advocate it as a norm, and it's the basis for public engagement.

It's like the difference in business acumen and attitude between running a million/billion-pound corporation, and a market stall. Yes, you can make money with both but they're hardly comparable in terms of profit, power, and influence. Yet magical thinking has Muslims believe that the market trader, in the aggressive world of unfettered capitalism, has a hope. If this line of thinking wasn't so widespread and tragic, it'd make for an award-winning comedy show.

The difference between village Islam and civilisational Islam has nothing to do with orthodox vs liberal/progressive - a false distinction made in defence of village Islam, but the extremely variant levels of engaging with orthodoxy. In fact, village Islam doesn't need to engage with the details of orthodoxy because it's meant to be simplistic. It all goes wrong because village Islam is ill-equipped to engage at such levels of depth and analysis. Such intellectual inquiry is inherently a civilisational undertaking.

We reliably see its bad effects across the board. For example, many jihadists (for lack of a better term) want change. But because village Islam has no constructive content (it’s about maintaining a simplistic version of subservience) they reductively proceed to destroy what exists merely to replace it with a medieval village. Many callers for “sharia law” are the same – their conception of doing "sharia law" is simply to re-enact village living. Yet, as the Hanbali legal philosopher Ibn al-Qayyim put it in I’laam al-Muwaqqi’in, ‘Whoever gives fatwas to the people merely from what has been related in books differing from the customs, habits, era, social/political circumstances and contextual variables, misguides others and is himself misguided. His injury to the faith is greater than that of a doctor who treats patients inconsiderate of their different customs, habits, era, circumstances and contextual variables, merely seeking to reflect what is in the general books of medicine. Such a doctor is an ignoramus, and such a mufti too is an ignoramus; both are the most harmful they could possibly be to the people’s religion and their bodies – may God help us!’

The vast majority of Muslims are afflicted with this quandary in some way: we’re told that “Islam is the solution” but none of us can see exactly how a village approach will resolve our problems, or the world’s. And no, I'm not merely referring to geopolitics, or the way powerful states influence others, but even to matters closer to home.

For example, we're plied with populist preaching and 'heart softeners' as if they'll constructively provide us a consistent godly resilience in modern life. Resultantly, people are taught to confuse an emotional spike with a way of being and outlook that correlates with God's account of reality. Or we're told that a 'good believer' is always studying and then sold immaterial courses on the particulars of hadith criticism, or the works of Ibn Hazm - entirely academic undertakings absolutely irrelevant to a modern godly life which is what the pitiable participants were actually looking for.

A practical example is where we're told women should stay in the home, take care of the house, and obey their husbands. But the village lifestyle doesn't work for those who live in metropolitan conurbations where astronomical prices means both men and women are forced into the workplace. So what inevitably happens is that a women works a 9-5 then comes home and takes care of everyone and everything, whilst the man does little to share the domestic burden (although she's sharing financial burdens).

Now there’s a refined and nuanced shar’ī way to discuss these issues that'll probably offend BOTH liberal and conservative sensibilities, but we've certainly not had them. Instead its polarised: it tends to be either village Islam, or a rejection of village Islam for secular liberal sentiments. A civilisational (high) shar’ī conversation is by-and-large non-existent in the public space.

These are mundane examples (to some). But the truth is that there ISN'T a realm in which village Islam isn't having deleterious effects today.

From our conceptions of God and the Law, to personal wellbeing, politics, finance or society, village Islam not only rules the roost but increasingly worsens every situation or fails to provide the direction needed. It's for this reason that I don't actually blame Muslims in politics: where village Islam offers little by way of political theory one will inevitably be drawn to other interests (in the name of Islam) such as ethnic minority rights and multiculturalism. And those who don't, end up on the other side seeming to associate with right-wing conservatism. What's heartening is that the intentions of many are good, but activists simply don't have the tools.

But what do you do when your leaders are actually the same as you, and most are no more sophisticated than village elders, or behave like shaman?

Recognise it for what it is and move out of the village. If you're not ready to, or you find it unsettling because it's unfamiliar, then you're free to village Islam but you're in no place to advocate it as the complete notion of what the Prophets delivered from God, nor should you bizarrely view it as an ambition.

Unpicking for Christians and Muslims

Dear good Christian and Muslim friends, there is great confusion on matters of faith and what it means. Much of it has become jumbled, and the simple and unadulterated message of God is sullied by conflations and mischaracterisation.

Allow me to unpick it for you:

1. Small "i" islām which is simply an Arabic transliteration (because the final messenger was Arabian) of the word subservience/submission, and denotes subservience to God according to the religion of Abraham. Another word God uses in the final ancient Arabic message alongside small “m” muslim, is hanif. It is coherent, consistent and appeals to common sense reasoning.

2. Big "i" Islam which is a proper noun and denotes the modern religious phenomenon popularly called Islam. It’s a mix of folk religion, intellectually reductive debates, ritualism, Mohamedenism, a superstitious outlook, and often an insipid mechanism for social control.

3. Cultural Islam which is an ethnicity and advocates ethno-cultural norms. Highly secular, in the western political/public space it either advocates multiculturalism or post-colonialism, and is habitually concerned with BAME. rights.

Also, please let me be clear: I advocate the only true religion (number 1), the religion of Abraham, and the law revealed to him and his descendants, with the final amendments revealed to the last of God’s messengers, Muhammad, descending from the tribe of Kedar, the second son of Ishmael and the grandson of Abraham.

I do not care for foreign terms but substance, and whether we use Arabic, Aramaic, Hebrew or Abraham's Sumerian or Akkadian to name it, is inconsequential. However, since I write in the Anglophone realm, English is the natural go-to.

I do not call my big ‘m’ Muslim friends, nor my Christians friends to modern and cultural Islam which has become another sect of Abraham’s religion (alongside Judaism and Christianity). The story neither started nor was defined by either Jesus Christ nor Muhammad, but with their forefather, Abraham the friend of God.

I welcome a conversation about what we all equally claim:

That we serve the One True God Almighty according to the understanding of Abraham and His descendants.

I don’t believe any sincere Muslim or Christian disagrees with this and once it’s explained as to where things went wrong along time, I’ve never witnessed a person not take the basic but pure path, whether scholar or layman.

As has been the case for thousands of years, the Prophets taught that practical subservience to God is built on declaring one’s allegiance to God, offering ‘prayer’, the giving of tithes, fasting and pilgrimage to the ancient sanctuaries. Beyond these, true believers have always sought to uphold Abrahamic law and morality.

And as Brits, I believe we all ought to celebrate Britain’s rich and old connection with Abraham’s faith and seek to revitalise it (accurately) in this great land of ours once again.

Men, wives and mothers

One of the identifiable causes of marital problems that are brought before me is the lack of independence many couples find with regards to in-laws. Either in-laws are persistent in trying to get involved in the workings of a spousal relationship, or spouses aren’t left to get on and live their lives autonomously. The parents of spouses can often present as a huge impediment to the growth and maturation of a spousal relationship: people need to fight, argue, make up (and make love); find common ground, learn to accept certain traits and seek to change other ones. There is no such thing as the perfect partner, but partners are meant to mould themselves and one another in an ongoing process of finding the best format for their relationship, and the types of people they want to live and grow with. God says about spouses “They are as garments to you as you are to them” (2:187) and like garments, even though they fit from the beginning, they can be slightly tight in some places or the material a bit itchy. But after they’re worn in, they become the most comfortable (and preferable) clothes in the wardrobe.

Life is about negotiating with parents, kids, friends, associates, colleagues. To assume everybody must change except you is the height of arrogance and narcissism. Real men seek to be purified (see 9:108), and you're only cleansed when you get dirty. Thus the real man is one that acknowledges that blame probably falls in his camp most of the time and seeks rectification. It is a highly blameworthy quality to always put the blame at other people's doorstep - problem solvers seek to resolve an issue, not run away from it and claim it has little to do with them.

In some ethno-cultures there is the assumption that offspring remain eternal slaves to their parents. Not only is the idea absurd it doesn’t reflect anything in the sharī’ah. Many confuse the idea of God exhorting people to be benign towards their parents “and lower your wing in humility towards them in kindness” (17:24) as somehow suggestive that the parents have the right to ‘everything’. Exhorting one party to be good doesn’t mean the other party suddenly has unfettered rights and access - that is simply illogical reasoning. God telling me to be good to a beggar doesn’t mean that the beggar suddenly has the right to my bank account and to take over my home. It’s simply a one-way exhortation in the interest of specific needs of the beggar. As a man, and obviously I speak from the male prerogative, to find yourself between your mother and your wife is not a ‘difficult’ position - it’s one that shouldn’t even exist. A mother should know the parameters of motherhood, and a wife the parameters of a spouse - and the two do not cross over, ever. If the respective parties are unaware of this or do not understand, it is the job of the man to (tactfully) cultivate each party so that they become aware. Running away from this task is not the ‘manliness’ that such people claim.

Furthermore, there is NO manliness (nor religiosity) in putting your wife down or making her miserable at the behest of your mother (or both parents), in fact it comes across as quite cowardly. And then in this ostensible state of cowardice to expect your wife to respect you or you ‘manliness’ is a bit of a joke - you haven’t exactly given her a reason to. It is no surprise how often I hear women telling me that they find it difficult to respect their husbands out of questioning his manliness. One might retort, “Well maybe there’s something wrong with her…” No, very simply, it should be beyond question. If you want to be the ‘King of the Castle’ or ‘Leader of the Faithful’ in your homes, then perhaps learning to act independently and in the interests of those under your charge would be a good place to start, whilst of course, maintaining a good relationship with mumsy.

Some men insist on acting like 10 year old ‘mummy’s boy’ and then ridiculously use their invented version of religion to legitimise their immaturity or lack of backbone. God exhorts to strength, confidence, aptitude and discernment. Those who demonstrate the aforementioned do not have mothers who treat them as boys; their mothers simply wouldn’t think to and intuitively know that it’d be out of order. To be fair, some males cannot be blamed (I’m differentiating here between men and males): their entire lives are controlled by overbearing parents where they’re not empowered to form the basic skill sets needed to make decisions - let alone good ones, or take care of themselves, let alone others. As a result, they lack maturity, incisiveness, discernment and the interpersonal skills required to navigate the complexities of life and negotiate favourable outcomes. (This also explains a lot about our political and religious ‘leadership’). The kind of absurd things grown adults offer as excuses in arbitration or when seeking advice from me is bewildering.

However, the wives of these men sometimes are no better, they complain about their husbands yet either act like their husband's mother (by being overbearing, babying him, emotionally blackmailing him, or undermining him at every turn) or raise their children in the same way - mollycoddling and infantilising their own growing kids. At the point of marriage, their sons are literally transferred from one set of cradled arms (the mother) to another (the wife’s). Not only is it embarrassing, it’s quite nauseating. If this bizarre cycle is to be broken then we must consider the following in raising our children - both sons and daughters: It is sometimes in the child’s interests to have their lives ‘controlled by adults, in complicated, age-dependent and sphere-of-discretion-dependent ways. What children should be free to decide for themselves will depend on their emotional, physical, and intellectual maturity. Nobody thinks that very young children should be deciding for themselves what to eat, where to cross the road, and the like. But as children get older, the kind of authority over them that is justified changes. *One learns autonomy in large part by practicing it*, so the duty to help children develop the capacity for autonomy implies careful judgments about when children are ready to start making their own choices, and gradually increasing their discretion over their own lives.’ (Brighouse and Swift, Family Values: The Ethics of Parent-Child Relationships, p.26)

As a parent, some of my proudest moments are not when my children simply do as I say, but when they intelligently disagree and posit a robust and compelling response. I once said to one of my children who sought a chocolate biscuit for payment, “Will you only tidy up because of some promise of a reward?” He said, “Why not, dad?” I said: “Isn’t God’s reward enough?” He replied, “That’s exactly what I expected - for God to reward me through you!” Cue silent dad, which doesn’t happen often!

Muslims will only rise to the challenge when they cultivate intelligent, autonomous, rational, godly and civilised beings, ready to take on the world on their own, able to take care of themselves and others, and think creatively. Raise problem-solvers, not adults who cower from confrontation or throw hissy-fits when things do not go their way. Not only does it inevitably cause misery rather than happy and resilient people, it’s certainly not the way of the believers.

"Go back to Pakistan" and the MCB's response

Very recently, Conservative activist Theodora Dickinson tweeted that if Labour shadow minister “Naz Shah hates this country so much why doesn’t she go back to Pakistan?!” This vile show of racism was in response to Shah discussing her experience of poverty. Of course, the foolish Dickinson exposed her racist impulses - here there is no doubt. Neither is there any doubt that Tories have continued to tolerate hatred towards Muslims as well as racism towards minorities.

However, the point of this article is to point out something we’ve highlighted for years, that the public conversation in the UK on Islam is being subsumed under the banner of being Asian, and most notably Pakistani and Bangladeshi. Whilst it's convenient to put this corruption on non-Muslims, the truth is that it’s driven by major Muslim organisations claiming to represent Muslims but who in reality use Islam in politics as a form of ethnic protest. The latest significant example is that of the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB). I am neither picking on the MCB nor do I claim that the organisation doesn't do good things, and here I differentiate between the organisation and its individuals (and the great things they've achieved). This post is about what the organisation stands/speaks for - as an organisation.

Now MCB's response to the Dickinson episode is unsurprising given its advocacy of the British Muslim APPG's definition of Islamophobia which subsumes racism towards Asians as anti-Islam. When I raised this previously, the MCB were quick off the mark to tell me this wouldn't be the case, yet as we suspected, that's exactly how the MCB has functionalised it.

The response of the MCB to the tweet was simple: by the racist Dickinson telling Shah to go to Pakistan (although the UK is her country) she was being Islamophobic. For the MCB, anti-Pakistani racism is anti-Islam - which obviously it’s not - it’s racist. This seemed clear to Shah herself who said, “Over the last few weeks BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic) communities have been coming to terms with the racism they have faced over the years. In 2020 to be told to go back to Pakistan highlights the level of racism that still exists in some quarters of society.” Note that Shah DIDN’T conflate the episode with Islam.

Pakistani is not Islam and for the MCB to make such a crude conflation says that either it is wilfully appropriating a religious identity for Asian interests, or that it is ignorant of what Islam and Muslim is in which case it has no legitimate claim to representing Muslims and ought to rebrand as the Asian (Muslim) Council of Britain. Please note that the issue here isn’t with being Asian - people are free to celebrate their ethnicities (and we like to join in!), but with how the MCB is diminishing the level of Muslim public discourse in the UK instead of rectifying it and raising it as is the MCB’s moral responsibility. And this issue would equally need to be raised if a mainstreamed Muslim organisation did the same with Somali, Moroccan, Nigerian or Albanian ethnicities.

As believers we are stoutly against racism, xenophobia AND political anti-religious hatred. But we also acknowledge that they’re not all the same thing (although they obviously coalesce in particular situations). And as believers, we must be concerned for the future and how such organisations are feeding into it - the MCB are frequently called upon by the media where it positions itself as a mainstream Muslim organisation but where it actually seems occupied with ethnic rights (obviously admirable in and of itself). And no matter how much we raise the problematic nature of the conflation or call on self-labelled Muslim organisations to be Muslim rather than something else, whether we do so in the open or behind the scenes (which I’ve done for years), the MCB doesn’t seem interested. To be clear, our only interest in this is God’s cause, what it’ll mean to be a believer in the near future for us and our descendants, and our moral obligation to deliver the message. No matter the circumstances THESE will ALWAYS take precedence to the sincere believers. Yet the MCB and other such public organisations seem committed to something else.

The current conflation of ethnicity and religion in the public realm is heinous in God’s eyes. It causes people to believe Islam is an ethnic identity specific to certain groups of people and their culture, rather than a natural (fiṭrī) inclination that enhances ANY culture and historical way of living.

God does not want to undermine British culture in the UK but to maintain it and bring out its best aspects. He wants the British people to be the best they can be, and the final Prophet of God showed us how to constructively situate the sharī’ah in any cultural context. Just as he did with the ancient Arabs, we too are expected to do so amongst us Brits. Calling to God is the believers’ priority, and where there’s a necessary contradiction, the narrative that promotes universal tawhīd (monotheism) and hanīfīyah (Abrahamic subservience) always takes precedence even if it means a negligible injury to ourselves or our ethnic interests.

Selfless commitment to God and His deen is what God calls to, and where we’re having an internal communal dialogue then yes, the matter is clear: “Do people think they will be left alone after saying ‘we believe’ without being put to the test? We tested those who went before them..”

No one ethnicity has more right to the Abrahamic truth than another, yet those deliberately making such conflations suggest otherwise. When believers speak in public then it’s clear: “Who speaks better than someone who calls people to God, does what is right, and says, ‘I am one of those devoted to God’?” (41:33) But not only is this call severely hindered, I believe the Establishment are very happy about it - they love to see a weak and unthreatening cause. The narrative that the MCB assist has meant that people literally tell you that they wouldn’t be Muslim because they don’t want to be Pakistani, or view the true religion of Abraham and the sharī’ah given to Muhammad as simply a foreign culture. Not only has something gone VERY wrong, the failure to actively counter this erroneous narrative demonstrates moral culpability.

Of course, to those who seem to have little knowledge of the final message (the Quran), the obligation of the believers, and the intersection between political theory and public theology, it’s not surprising. So rather than separate the pristine sharī’ah from what taints it (all cultures are fallible with problematic elements), the MCB has been adamant not to do so. The very simple point seems lost on the MCB that you cannot suggest Asian and Muslim are the same thing, but then when Asians do things you don’t like (like in Rotherham) you argue that it’s not a Muslim issue and calling it so is Islamophobic, then you’re clearly not getting the optics.

Allegiance to God and the godly cause, which the MCB seems to conflate with contemporary social justice activism and the interests of the Asian community, compels us to challenge such state of affairs. (Of course, a shar’ī approach includes social justice, but our activism is shaped by shar’ī objectives and variables.) Again, were it not for the damaging consequences of a major organisation in the public eye misrepresenting the Muslim cause, posts like these would be unnecessary. But alas, they stray into territory that necessitates it.

For clarity, here are some of the ways in which this is a grave problem for those committed to the advocacy and spread of Abrahamic monotheism and the sharī’ah (da’wah). It undermines:

- The call to true Abrahamic monotheism free from foreign cultural baggage and an ethnic character

- The basis of a public conversation that starts with revelation rather than defending against ethnic conflations

- The presentation of God’s final word that sits within the British cultural context

- Legitimately locating problematic ethnic attitudes and shar’ī rectification required within ethno-cultural communities

- Actual anti-Muslim hatred face by believers of various heritages

If Dickinson had told a Nigerian/Malaysian to go back to Nigeria/Malaysia, would the MCB have called that Islamophobia? Probably not (and of course, it wouldn’t be). Either Muslim organisations must stop using Islam as a shield for ethnicity-related issues, or we must accept that being a Muslim in the public realm is basically to be ethno-cultural. And if the latter is true then we can't blame believers who'll refuse the Anglicised appellation of 'Muslim' or rail against its misuse. If such organisations refuse to listen or chart a course built on both shar’ī and social knowledge, how long do we go and how perverse must the public discourse on Islam become until we say, “Not in our name?"

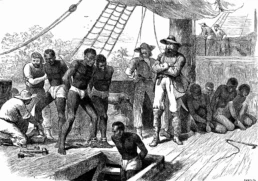

Muhammad didn't have ‘slaves’

In this post I’m not interested in what people do or have done, but with normative shar’ī prescriptions. Whilst I’m not surprised by the ignorance or wilful misrepresentation of some (like Douglas Murray), believers ought to know some facts. Controversy is only controversial due to ignorance. I don’t provide a justification for medieval slavery as there’s no need to. This post is simply a very basic clarification for believers.

- We believe that there is no ultimate submission except to the one true God, Lord of Abraham and his descendants: Moses, Jesus and Muhammad, all of whom were God’s noble slaves. In the sharī’ah, we only recognise slavery in the context of slavery to God. The Prophet put it, “None of you should use the term ‘My male or female slave’ since all of you are the slaves of God and all your women are the slaves of God. Use the terms ‘my servant (ghulām/jāriyah)’ and ‘my boy/girl (fatā/t)’." (Muslim)

- The sharī’ah does not legitimise ‘slavery’. The term slavery today refers to a distinct English concept shaped by the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Hence the idea that the messengers of God either practiced or authorised slavery is both erroneous and anachronistic. As I’ve written before, when discussing the sharī’ah we ought to stick to the shar’ī terms God sets out as closely as possible, they are most accurate since it is how God and His messenger described and taught an issue/concept. Often, English words that are used to represent shar’ī concepts are assumed to be the closest resembling words but not the exact thing, rarely are they conceptually the same.

- What the sharī’ah did permit, albeit seeking to diminish it through a gradualist approach since liberty is the greatest value, was riqq – a form of servitude that provided unfree labour and obliged housing, clothing, food, etc. It was neither racialised nor the product of racial supremacy, many were Arabs themselves, as well as from the Roman Empire, Africa and Asia. The Prophet characterised the raqīq, saying, “They are your brothers who God has placed under your charge. Feed them from what you eat and clothe them as you clothe. Do not burden them with what they cannot bear, and where they are overburdened, help them.” (al-Bukhārī and Muslim) The raqīq was considered an extension of the household (for example, a woman’s awrah in front of her raqīq would be like that of her male family members) and as the hadith intimates, expected to be treated this way.

- Did the Prophet encourage owning a raqīq? Well notably, when his daughter Fatimah requested a khādim (domestic servant) for help with the home he taught her godly mindfulness (adhkār) instead. As for those who did have riqāq (plural of raqīq), he encouraged two things: good treatment whilst under their charge, and emancipation.

- In the sharī’ah, the way to free a raqīq was to purchase his or her freedom. This means buying them and setting them free. So at this time, everyone who sought to free a raqīq would own them, even momentarily. And after emancipation the raqīq would be considered something like extended family, a term in ancient Arabic known as mawla.

- Muhammad, the Prophet of God, was neither a slave owner (however benign the misguided make out his so-called ‘slave owning’ to be) nor a slave trader. And neither was he a raqīq trader. He obtained individual riqāq through two ways: either he was given a raqīq as a gift or he bought them, coming to free them all. al-Nawawī stated in a well known position that they were the Prophet’s riqāq individually, and at separate times. What this suggests is that he doesn’t seem to have simply been a raqīq ‘owner’ in the sense that he had scores of riqāq concurrently for the sole purpose of ownership. Successively obtaining an individual raqīq can suggest that the Prophet intended to obtain riqāq for their eventual emancipation. It cannot be said that he did this because he might have looked bad; being the leader of Madinah, he could have had a band of riqāq and nobody would have raised an eyebrow for something quite ordinary and expected at the time.

- So while the Prophet freed some riqāq immediately, others he did so after a while. But why the delay? There are variant reasons and possibilities: there may have been mutual benefit in their association; that the raqīq didn’t want to be emancipated just yet; the raqīq wasn’t in a financially and socially stable position where freedom would have meant destitution and/or homelessness; the Prophet wasn’t immediately in a financial position to help the raqīq post-emancipation so waited until he was. We know that it wasn’t always in the interest of a raqiq to be legally emancipated as he or she would then be left without support. In a telling hadith related by Abu Musa al-Ash’ari, the Prophet said, “Any man who has a walīdah, educates her well and nurtures her well, then emancipates her and marries her, shall have two rewards.” (al-Bukhārī)

There are variant opinions on the names of the Prophet’s mawālī (plural of mawla) as there were some ṣahābī emancipated by the Prophet but contractually obtained by others. Some of the notable mawālī of the final messenger of God:

- Zaid b. Hārithah was obtained as gift to him by Khadijah, emancipated and then adopted as a son. An Arab, he was well known amongst the Quraish as one of the most loved by the Prophet and was referred to by name in the Qur’an (33:37).

- Abu Rāfi, a Copt, was a gift to the Prophet from his uncle Abbas and emancipated. Once, he was about to receive some ṣadaqah, but when he asked permission from the Prophet, the Prophet replied, “The mawla of a people is one of them, and ṣadaqah is not permitted for us.”

- Thawbān b. Bujdud, a Yemenite Arab, was taken a captive of war in jāhilīyah (pagan times). The Prophet bought him and freed him, but he served the Prophet until he passed away. The Prophet once told him not to ask anything of anyone, and he complied to the extent that if something fell from his hand he wouldn’t ask anyone to pick it up for him, or even pass him anything.

- Abu Dhumayrah was a Himyarite Arab whom the Prophet bought and emancipated. The Prophet had Ubay b. Ka’b write a letter in his name that exhorted believers to be good to Abu Dhumayrah and his family which his descendants kept and famously presented to the Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi who gave them 300 gold coins (dinars).

- Abu Muwayhibah: The Prophet brought him and freed him. He narrated the famous hadith on the Prophet seeking forgiveness for those buried at the Baqī’ cemetery.

May God's peace and blessings by upon his noble slave and final Messenger.

Race, Ethnicity and Community: Where do we go?

It’s simplistic to argue that religious spaces need to be inclusive when we factor in that these spaces are less ‘religious’ than they are significantly ethno-cultural and sectarian - intended to protectively maintain an ethnic and denominational environment. Resolving feelings of marginalisation and prejudice won’t simply boil down to addressing anti-blackness and racism in ethno-cultural communities. There’s much more going on and much of it interrelated. Having thought about this issue and how to proceed effectively for a while, and trying out various things on the ground, here are some conclusions which I briefly explain.

Racialisation, Muslim spaces, and ethnocultural communities

In order to meaningfully discuss the ‘black experience’ in British Muslim spaces, there are a few things that we need to consider. There are many things to unpick, a few of which I attempt here:

1. Communities in the UK often characterised as religious are in fact ethno-cultural; an ethno-cultural community is one that believes it’s ethnically or culturally distinct from other groups. In what way? In its cultural practice, tradition, solidarity, and (can include) religious outlook. If these Muslim communities are in fact ethno-cultural, which ethnicity predominantly? The statistics show that the vast majority of ‘Muslim’ communities across England strongly identify as South Asian, where Islam is an aspect of their South Asian cultural heritage. (I refer to a broad South Asian characterisation here merely because the sub-cultures are similar and exhibit a greater level of solidarity to one another than to others, and I also distinguish between believers of Asian-heritage and those who primarily identify as South Asian with a deep commitment to cultural values.) This has led to the widespread conflation amongst Muslims and non-Muslims that ‘Muslim’ and ‘Asian’ are synonymous. This false conflation allows for:

(a) the perpetuation of the ‘black experience’ in communal ethnic spaces to be seen as a ‘Muslim’ problem when they’re not: “Muslim communities are racist…”, and

(b) misleads racialised ‘black’ (and other non-Asian) believers into seeking a sense of belonging with ethnic communities inaccurately taking them to be faith-based ones.

What many people overlook is that the ‘black experience’ of believers is often far more pronounced in South Asian spaces (due to its conflation with being a Muslim space) than wider society and many will affirm that the first time they experience overt racism and/or prejudice is amongst South Asian Muslims. Now if wider anti-Black prejudice affects the opportunities of the

marginalised, then prejudice and marginalisation faced by racialised believers that affects their faith is even more problematic, and that’s my interest here.

The impact of ethnic motivations on ‘Muslim spaces’ has resulted in the following:

- ‘Muslim spaces’ are highly racialised as South Asians tend to have a strong sense of ethnic identity in comparison to others. For a mundane example, “Where are you from?” is the opener for most conversations.

- Just like ‘white’ is viewed as normative in wider discourse, South Asian customs and attitudes acquire a presumed normativeness around all things ‘Muslim’. The culturally insular nature of South Asian communities also means that in reality, Muslim spaces are firstly South Asian spaces. I am not problematising this (as it’s somewhat inevitable) but it’s important to recognise for the purposes of these posts. Under these circumstances, when issues such as ‘Muslim unity’ is raised, what is meant de facto is an accord centred around South Asian norms, values, interests and approaches – both social and political, and in most situations the promotion of unity and/or the empty platitudes of “Islamic” utopianism merely maintain a (usually South Asian) ethnic dominance of the Muslim narrative, along with immigrant interests. To a far lesser extent this also happens in non-Asian communities that present a normativeness based in a historically and culturally specific ‘Immigrant Islam’.

- In the public realm, ‘Islam’ and ‘Muslim’ is highly politicised both by Muslims and non-Muslims. Due to their own misperception that merges ethno-cultural commitments and religion, they identify as Muslims through the lens of multiculturalism adopting a secular expression of Islam to maintain their interests under political liberalism.

2. Keeping these brief points in mind we must recognise then that the unity and sense of belonging many believers seek is not to be found in this context. It is a misplaced aspiration and one based on a mythical notion of sameness. The uncomfortable reality is that we all don’t share significant capital. So whilst one may support local Gujrati and Turkish communities in the preservation of their civic rights just as he would other ethno-religious groups, he’s wholly conscious that he’s not a member of their respective ethnic communities and that their mosques, schools and cultural Muslim centres exist to serve their own ethnic groups, of which he’s not a member. They may kindly permit him to use their facilities for salah at specific times (many kind Christians have also welcomed Muslims to use their facilities), but he’s not lulled into a false sense of belonging and/or community. One may acknowledge that in many situations, it’s not that they have sought to actively marginalise those unlike them but to maintain the dominance of their own cultures in the spaces they consider to be theirs.

Unfortunately, many ‘outsiders’ are easily caught up with superficial claims of unity and/or sameness, but the existence of these communities isn’t premised on faith as the overarching identity – faith is subsumed under the greater umbrella of their own ethnicity. This of course does not justify racism and colourism that may emanate from these ethnic communities, but we need to

acknowledge that these spaces simply aren’t for us, and never were they meant to be. To expect shared religious and cultural capital with those from intensely insular ethnic communities is highly misplaced. And the reason much of this is not said, although intuitively acknowledged by most, is because ‘outsiders’ are reticent of being charged with ‘disuniting’ Muslims, and many of these communities are apprehensive of exposing the reality of their ethnic commitments and allegiances.

3. Now to be clear, my point isn’t that racism/colourism doesn’t exist in such spaces, but that we need to unpick racism from ethnic preservation – is it ‘Muslims’ being racist, or South Asian’s preserving their ethnic identity which happens to include religious practices? From a point of faith-based interests in the UK both are problematic, but for very separate reasons. For a case study of this conflation: there are complaints of the ubiquity of Urdu in communal Muslim spaces such as Asian mosques or seminaries with the accusation that this marginalises non-Asians, but we fail to realise that these spaces principally exist to promote distinct cultural values and (subcontinental) Asian Islam. Even where the argument is made that it’s about denominational commitments such as Deobandism or Barelvism and not ethnicity, the reality is that these are specifically ‘ethnic’ denominations and modes of thinking vis-a-vis the Asian immigrant experience. In real life this is borne out: neither do Deobandis nor Barelvis seem to envisage non-Asians converting to their denominations, nor do cultural ‘outsiders’ on the whole find these denominations particularly compelling or enticing.

4. In the interests of fairness we must be nuanced. Anti-Blackness is deeply entrenched in many structures and cultures so we ought to acknowledge that many people do not know how to recognise anti-Blackness and its various manifestations, nor have they lent a conscious thought to the ways in which they might subconsciously hold racist views that contribute to the ‘black experience’. Whilst it is true that we cannot hold all racial offenses of all people to be intentionally racist (whether they’re South Asian, ‘White’, or whatever), we can hold them to account when it’s brought to their attention, and current events afford us even less of an excuse. As many have witnessed, often there is a strong resistance to change which exposes how deeply entrenched racism is. Some of the following act to impede change:

- ‘Asian fragility’: a profound sensitivity around highlighting racism or prejudice within Asian communities, often dismissed or deflected onto older members: “It’s only the older generation.” And the preoccupation with maintaining a positive view of ethnic-self means that there’s a white-washing of the past and little resolve to consider it, namely the impact Hindu heritage has had (such as the Indian caste system) on their current norms and values.

- Hypocrisy: Many South Asian communities will criticise ‘whites’ for their racism, even joining the movement against anti-Blackness but then do exactly what they accuse ‘whites’ of. Aside from whitewashing their past, many will refuse to speak out or challenge wildly racist sentiments in their own communities whilst expecting ‘whites’ in the same situation to do so. Many will acknowledge the structural racism in their institutions yet remain committed to upholding those structures whilst denouncing others for not tearing theirs down. Many underplay anti-Black microaggressions whilst protesting the same microaggressions in wider society when perpetuated against them.

- Either a complete denial of racism such as “I’ve never seen it/we don’t think we’re superior”, or an absurd counterclaim based on a generalisation that isn’t even made: “You’re a racist for calling us racist.”

- Justification with even more racism: “We’re not anti-Black, but Blacks do commit more crime…”, or “You just sound angry” feeding into the Angry Black Man/Woman trope.

- False retorts: “You’re calling us racist just because we won’t let you marry our daughters” when the anti-blackness goes far beyond denying marriage.

- Whataboutery: “But what about [insert another ethnic group]?”

5. The complexities of social change means that because so many distinct variables are interrelated that to change one significant thing can necessitate rethinking the entire structure. In the next post I discuss what I mean by this. It is easy to say that we simply need to inform Muslims about “what Islam says” since what it means to be a Muslim as well as our views on

subservience to God and what it necessitates across the board can wildly differ. Furthermore, we assume that simply making people aware of their implicit biases will change them, but there’s a lot to suggest that it doesn’t work like that. So what to do? In the next post I discuss possible answers and certain realities.

Believers and the ‘black experience’

Before moving on to discussing the 'black experience' in private communal contexts (mosques, Muslim spaces etc), it is important to differentiate between two different things:

- a black identity - internal representation of an individual based on colour

- the ‘black experience’ - external (shared) treatment of an individual based on the perception of others. It comes from being racialised as ‘black’ which then becomes the basis of prejudice, inequality and marginalisation.

As I’ve made clear, I’m coming from a shar’ī Abrahamic perspective. As for those seeking a lens or a sense of self-determination from other sources, then as always one is free to do as they see fit. But I share with those believers targeted with the black experience an entire outlook on how to view (and identify) ourselves, the world around us, and the best ways we proceed in any given situation - all deeply informed by God’s account of reality gleaned from revelation. What I write in these posts relate to this.

Please note, I’m trying to keep these posts

extremely brief and I acknowledge that they do not address many of the possible

contentions that may be raised. Hopefully, I’ll follow up and clarify elsewhere

for those interested.

A black identity

A ‘race’ is a social group based on arbitrary characteristics. A black identity is a political one, it is not a positive one: calling someone ‘black’ (or identifying as such) doesn’t tell us anything about a person’s language, culture, values, norms, outlook, or relationship with God (and yes this also goes for a ‘white’ identity although this identity was created to denote something positive in juxtaposition to being black). It denotes an experience rooted in marginalisation, being subjected to prejudice and discrimination, and racialised brutality. The assumptions behind the racialisation are fallacious: those racialised aren’t homogeneous: skin tones and hair types vary, so too do languages, faiths and cultures. If one says it’s based on those who look ‘African’ then what’s being missed is that Africa is a colossal continent with thousands of groups and languages, and people who look entirely different across it. If one asserts that it’s about people of African heritage, then *newsflash* we ALL have that heritage somewhere up the line, no matter how straight your hair or light your complexion. What’s interesting is that most people in Africa do not identify as ‘black’ nor internalise 'blackness'. Before European colonialism diverse sets of people usually identified with their tribe or nation (a common language and culture). Those from the African continent who do so in more recent times have done so as a reaction to being invaded by white supremacists and being designated black by those supremacists. It is a nefarious pigmentation-based designation meant as a defining value of the human being.

So how do believers relate to this imposed identity? Well given that it comes from a disbelieving (kufri) mentality that groups all of these independent and diverse humans into one category (initially for the purposes of maltreatment which still informs its use) then to use it as a pervasive means of reference, or internalise this kufr-inspired proposition as a means of realising a self-identity, seems flawed.

The truth is that in a neutral (and thus normative) setting, people would NEVER identify as black if such racialisation wasn’t imposed on them by the disbelievers and would find it quite bizarre. What we ought to keep in mind is:

- As believers, we should NEVER allow disbelievers to dictate or shape how we view ourselves.

- To assume that we shall find ultimate emancipation in the very same label and associated identity used for our subjugation (i.e. blackness) is strange. And taking on the term but with an eye to alter the negative connotations seems misplaced, since (a) we still end up reducing ourselves to pigmentation which no one else does, (b) we remove ourselves from the context of a profoundly meaningful and greater human history God places us in, and (c) the linguistic baggage around ‘black’ is profoundly entrenched.

- It is offensive to God that skin complexion affords us any understanding of a human, let alone end up being a totalising one. This overwhelming delusion doesn’t just underly many societies, but as a reactive measure has become embraced by those dehumanised by the entire racialisation project. No other groups of humans self-identify by their pigmentation other than those disbelievers who gave 'blacks' such a designation (white supremacists) and locate a sense of supremacy in the entire project.

The black experience

So am I saying that calling someone (or yourself) ‘black’ is ultimately wrong or inaccurate? Not necessarily so (and it’s a tangent to be unpacked and discussed elsewhere), but *before* we progress to discussing the use of terms and what we mean by them, we FIRST have to recognise what it is we’re talking about or attempting to internalise. (I acknowledge that there is a difference between something being a limited physical description and an identity.) My only point at this juncture is to question the idea that believers either confer or internalise an identity based on ‘blackness’.

However, this is not to deny the black experience - that some of us are racialised as ‘black’ by others (since we did not choose this designation for ourselves) and face negative treatment as a result, some of which I detailed in the previous post. And I think that it is reasonable that those of us who share this experience might be drawn to some sense of likeness as a result.

So what does the shar’ī Abrahamic lens mean?

Well in this context, it means rejecting the characterisations of supremacist disbelievers, not internalising them - the Prophet of God would never allow the leaders of disbelief (a’immat al-kufr) like Abu Jahl or Abu Lahab negatively define the believers (whether it was by their pigmentation or anything else), and yes, they actually tried to do so with respect to Bilal b. Abi Rabah, Ammar b. Yasir, and other notable prophetic companions (ṣahābah). But avoiding the internalisation of an identity in no way means negating an experience, and as believers we are committed to dismantling the structures that create the black experience (as well as any other form of jāhilīyah). And rightly, this moment is about the 'black experience', just as there are other moments where the injustices others face are raised. Bringing up every other cause in this moment, or attempting to generalise this specific struggle with "all lives matter" is simply a nefarious attempt to undermine this one.

In our view, where are we ultimately going?

The activism God calls us to, is to work towards an environment that is conducive to tawhīd and hanīfīyah (monotheism and Abrahamic values) – the higher objective of any shar’ī activist. What mustn’t be lost on the believers is that anti-racism is not merely a goal in and of itself: racism (and colourism) are symptoms of shirk and jāhilīyah (shirk inspired culture) which are the foundations from which this problem has arisen. My point in this post is not to undermine work towards achieving greater equality in our society, but to point out to believers that our mission is twofold: that we seek to weaken what creates the 'black experience' in our society whilst keeping in mind that its ultimate cause is a jāhilī mentality which can only be holistically remedied by an Abrahamic outlook. This is how we plan to meet God in the afterlife.

For those with a godly outlook, since the age of the ancient Mesopotamians (and even before), alongside our respective tribes or peoples we have identified as those who have submitted to the one true God: “Strive hard for God as is His due: He has chosen you and placed no hardship in your faith, the religion of your forefather Abraham. God has called you submitters (to Him) both in the past and in this (message)...” (22:78)

Now some will understandably say: “Well Muslims can be racists, so religion doesn’t work here.” Some points in response:

- I’m not calling to ‘Muslimness’, I advocate the religion of Abraham as Muhammad the final messenger of God did. This is not a 'religion' but a totalising lens with which to view oneself and the world around us. The response is based on a faulty understanding of subservience to God (with which I can sympathise due to religious illiteracy) which views deen through an anthropological lens and boils deen down to what people do, not what God says. It’s also a racialised perspective where your faith is what you inherit rather than what you are compelled by, and it usually comes from those who feel that they cannot compel others from a shar’ī perspective. But this then says more about them than the strength or weakness of an approach.

- For some, this response is motivated by a stronger belief in the efficacy of secular approaches (whether liberal or post-colonial) than the sunan (ways) of the Prophets. It’s not that they don’t believe in shar’ī constructs, but they either engage with them as mere theory, or they think that people won’t accept them. But perhaps if they put in *as much effort* into learning shar’ī outlooks and educating others with it as they do reading books on anti-racism activism and working with it they’d see the difference they’re dubious about. (Please note that there’s a lot of good work out there on anti-blackness and how its perpetuated which ought to inform our work.)

- People who call themselves Muslims do not represent the values of God’s Law and Way unless they internalise and live by them. As for those who demonstrate or internalise racism, the term Muslim doesn’t make them any less jāhilī (paganistic), and they require education and confrontation just like anyone else. We have the choice of confronting them with either secular informed or shar’ī-informed anti-racism activism. Ultimately, the former uses social pressures whereas the latter employs these along with a remedying account of reality from God which is far more transformative across the board, whilst resolving inevitable challenges that arise in the process.

Qur'anic thoughts on colour and ethnicity

Race, ethnicity and nationality are all matters that are highly conflated in popular discourse. These posts attempt to unpick them before moving on to social ramifications and politics (in the context of the UK) in order to provide a very basic and structured account from first principles.

What is a 'race'?

Shar’ī-inspired anti-racism activism

Given current events in the US and how it’s galvanising

people here in the UK, I’ll be sharing some shar’ī inspired thoughts on race,

prejudice, and political activism.

As ever, I speak to a British context not an American one,

and I’m fully aware that what I may say about things in the UK will probably be

inadequate for an American context, not to mention the unique struggles of

African Americans.

For brevity, I won't be unpacking everything I post into

bullet point form although I will try to be as clear as possible. Please try to

understand that there’s a lot behind these posts, and just because I’m making

one point, it doesn’t mean I’m being binary or negating other things on the

spectrum.

Now, there are various perspectives to approach and deal

with anti-racism:

- Secular liberal

- Post-colonial

- Shar’ī (Abrahamic)

The nature of these posts is to expound on a shar’ī and

Abrahamic perspective.

I acknowledge that even within the shar’ī perspective, there

are competing and divergent modes and interpretations of the prophetic way.

Some are reductive, some misinformed, and some heavily concentrated on specific

points/prophetic events, missing the bigger picture. I acknowledge everyone’s

trying their best, and the intent behind my posts is the hope to develop the

nature of the conversation.

Some might respond with the customary: “Well you have no right to do that, just listen!” But such a response is misguided for those committed to the shar’ī (Abrahamic) perspective and speaking to one of their own, and whilst perfectly legitimate for liberal and post-colonial approaches, it overlooks our attitude that frames it as a group of believers mutually working together to constructively address the experience faced by some of them.

For a simplified characterisation between (1) the liberal and post-colonial approaches and (2) the shar’ī (Abrahamic) one, the following puts both approaches in a grievance and response formula:

- “Look what they do to us.”…“That’s injustice, just tell us what to do to help your community/people.”

- “Brethren, look what they did to some of us (believers).”…“Glory is only for God (Subhanallah)! What they have done offends God and takes the ways of pagans (jāhilīyah) whom the messengers of God were sent to guide or resist, so we too shall do the same. What they have done is done to us all - let’s strategise the best way to proceed.”

Now the point isn’t to silence raw emotions nor negate how subjected people might feel but we must realise that there are variant exercises depending on the objectives of the conversation. There is the initial listening exercise to hear the grievance and condition of those being offended, and then there's the strategy as to how we all (the believers) can collectively deal with the affront and reinforce one another like “a well-compacted structure” as God puts it.

I’m cognisant that there have developed so-called “correct” ways of talking about things. On one side we have those who police what ‘black’ expression and protest should be like according to what makes such monitors comfortable, and on the other there are approaches by specific (Black) groups who demand compliance to their narrative, as if to homogenise all racialised blacks and the approaches they take on these issues. Of course, liberal and post-colonial approaches have a great deal of valuable insights we ought to consider, but everything that we might take on board is framed within an Abrahamic context and God’s account of reality, since God’s guidance is the only true guidance.

I understand that many will still find what I’m saying here

to be somewhat ambiguous: “What does he mean and what’s he saying?” And with

that comes the hesitancy to engage with me in a neutral fashion. Hopefully, the

following posts will begin to illustrate where I’m coming from. In these posts,

I may challenge some of the approaches believers have instinctively adopted,

but it’s to do with constructively moving forward as believers. Again, my first

principles to such issues are taken from the sharī’ah, so whilst there might be

an ‘anti blackness solidarity framework’ from which to discuss things or

approach them, believers are not morally obliged to adopt it, nor acquiesce to

it. And yes, I’ve used the term “we” because I do not differentiate between

believers - if they’re targeted and mistreated, then it’s our concern.

Whilst believers ought to support anti-Jāhilīyah (regressive ideas that

ultimately source from paganism and superstition) movements irrespective of

faith, our fraternal bonds with true believers are naturally stronger with

those who are subservient to God in the way He wills it, and the more in-sync

that outlook the closer those bonds will naturally be.

Please note that these posts do NOT discount wider

solidarity with non-believers who experience immoral prejudice, I’m simply

focusing on what a wider shar’ī agenda compels us to consider. Whether it’s an

Abrahamic framework or it comes to wider solidarity, whatever we do is focused

from, and tempered by, the Abrahamic ways and a godly outlook to which we invite

all. That’s our fundamental basis in all things.