Reforming the sharia? A misplaced idea

The reason any discussion of reforming the shariah is misplaced is because the statement assumes the shariah to be an entirely static construct. We do not need reform, but where we might be struggling is with a real-time application considerate of all variables. The issue is that for all of the talk of implementing of shariah, we hypothesise what the shariah might look like, and even when many western Muslims speak of contemporary application they merely resolve to focus on the Middle East.

But what is being overlooked is the manifestation of the shariah that is principled on what God wants, and moral directives in the context of being western Muslims. It's not just about the shariah but how its values inform our discussions and offers meaningful ways to react, suggest and progress.

Moving forward and actualising faith today

I have written before that I believe today's believer can:

- be committed to the Quran and the sunnah without being salafi;

- benefit from a mad'hab without immaturely pledging allegiance to it, building an identity on it, or viewing everything through the lens of fiqh;

- have an aqidah that isn't polemic and reactionary but inspirational and imaan based, strengthening rabbaniyyah (godliness) and wara' (piety);

- be introspective and build a personal relationship with God where God is an active participant in one's life without ascribing to sufism;

- be politically active/aware in a way that goes beyond anti-colonialism and without the baggage of last century's Muslim political movements;

- be socially integrated in society without losing their faith or having their fundamental godly practices restricted.

Sajid Javed, countering extremism, and singling out CAGE/MEND.

We live in age where it seems no longer to be the norm that politicians and governments, even of the liberal democratic sort, shy away from open authoritarianism. In what should be a chilling demonstration for what's up the road, and in what is seemingly the pattern amongst troubling Tory Home Secretaries, Sajid Javed recently made clear some of his views in a speech on confronting extremism at the Coin Street Community Centre in London, on Friday 19 July 2019.

Here I’d like to make a few brief points about the contents of his speech. This is not a defence of the Muslim organisations he criticises since (1) I’m not privy to the full background of his criticisms, and (2) all of the criticised organisations have official spokespersons who are at liberty to provide an accurate defence/refutation on their own terms (I wouldn’t want to misrepresent them). My point in this post is to highlight the worrying nature of the Home Secretary's speech in light of wider political events and the things we (the British public) are generally aware of. Whether you agree or disagree with the Muslim organisations he turns his attention to, his speech seems not only unfair, the ramifications are extremely disturbing.

Thoughts on scholarly studies and methods

I often thank God for my learning and educational experiences. I never had a teacher who expected that I simply rote-learn, that I memorise the writings of others with the intent to regurgitate it when asked a question. One teacher once counseled me not to memorise texts written by scholars, but to aspire to become a scholar with his own authored texts. Every single tutor or teacher I've ever had expected me to critically engage the issues being studied, understand where jurists, historians, theologians or hadith scholars were coming from, to pinpoint the locus of the issue, learn to identify the operative variables, consider the function of the discussion in the real world, and form holistic opinions in light of everything else I ought to know.

I benefitted from them greatly and I've always considered the reasons as being:

Meditation Fads and Salah

God, in His infinite knowledge, created humans with particular strengths and weaknesses. He instituted specific core practices that'd keep the human mind, body and spirit in an optimum state. Amongst those things is the Salah, ordained for humanity since the earliest times.

Even over my own short lifetime I've seen a thousand fads and moral panics inconsequently come and go. It is the nature of humans that they move with schizophrenic tendencies from one hype to the next, "man is ever hasty." (17:11)

This is one of the reasons I rarely delve into an academic appraisal for the public on social media. Although it can be tempting to do so and I'm constantly requested for commentary on xyz, the influence of fads are usually fleeting and the engagement meaningless ten minutes later. Moral panics pass as soon as another rears its head. Stringently refuting fads (let alone ideologies) is time consuming and doesn't constructively imbue believers with something meaningful that'll afford them longevity - action informing guidance that'll direct them long in the future (which I'm more interested in). By engaging the latest ideological hype I feel I'd simply be running from pillar to post - the definition of firefighting rather than building. Liberalism, feminism etc all have their shortcomings, but rather than spend the limited time I have educating people about those ideologies I'd rather teach what God says and what operationalising His message might contextually look like. Anti-liberalism/feminism won't get you into paradise, but a meaningful conception of the shariah might (depending on your commitment and soundness of heart). And by knowing what to do, you'll intuitively and reasonably know what to avoid. Two birds, one stone.

But yes, I digress.

What is God centeredness?

It's a concept that resonates with every believer, a cognitive station to which the sincere aspire - to have God at the center of everything they do. It's not merely a principle or a concept but an entire attitude that puts God first, that posits His primacy, where the believer is perpetually engaged with the question: "What does God want here and now?"

Of course, to answer this question effectively requires knowledge, experience and godly intuitions. But these are not necessary to engage the question, they're necessary to answering them with some cogency. How you address these questions will simply depend on your circumstances, and for the vast majority of believers it'll be to consult the people of learning - those whom they've invested the resources in to provide them with the complex answers required today.

For me, a great example of God centeredness, and one that left a lasting impression on me, was the response of the true Prophet of God, Muhammad, to Musailamah the false prophet (as narrated by Ibn Hisham et al).

Musaylimah had written to the Prophet seeking to make an equal claim to prophethood:

I have been made your partner in the matter of prophethood. Half of the land belongs to us (Hanifah tribe) and the other half belongs to Quraysh. However, Quraysh do not act justly.

It was a move to solidify the power of Musaylimah and the Hanifah tribe over the Najd region, whilst attempting to ensure that the Prophet would restrict his 'reign' (as Musaylimah saw it) to the Hijaz.

The spectacularly noble and theocentric response of the Prophet was this:

This is a letter from Muhammad the Prophet of God to Musaylimah the Liar. Peace be upon the followers of guidance. The earth belongs to God, He gives it to whomever He wishes of His pious servants - and the pious shall meet a good end.

The Prophet didn't engage in a personal war of words, nor reduce His noble mission and the status God gave him to vying with a miscreant over some land. When Musaylimah made a claim over a part of the earth, the Prophet simply reminded him that the affair was bigger than any human being, and that the land which he was attempting to claim belonged to nobody but God, and that He alone decides who shall be invested with earthly authority. In that moment the Prophet wasn't overcome by emotions, nor personal interests, but broached Musaylimah's challenge with a godly lens.

After years of contemplating this prophetic event, I'm still in awe of how perfect the response was. A short statement that said so much: it inferred that Musaylimah was using the guise of prophethood for personal gain, that he actually cared little for God, and that in contrast, Muhammad's mission was not of his own nor to raise his own status but simply to raise high the word of God. Had Muhammad not been a true Prophet of God, he would've responded in like, seeking the land for himself and engaging in an egotistical polemic against Musaylamah. But the response centered solely on God, a pure tawhidic rejoinder.

Now considering this response compels us to evaluate how we do faith. Is God at our center? Are we obsessed with what God will say, or more worried about the community and other peers? Do we view orthodoxy as what pleases God, or what merely keeps us as bonafide members of the in-group?

When we speak on matters of the faith, is a debate on fiqh or aqidah issue about pedantic and technical minutae, or an exploration of what God ultimately wants where we're somewhat confidant in meeting Him with sound justifications? How much of our Islam is actually islam (subservience) and how much a social construct put on show to demonstrate allegiance to a group of people? What are our personal interests and/or allegiances, and where does God come in our 'religiosity'?

Jinn possession and scholarly opinions. Part 5

In short, what I’ve presented in this very brief series summarises the nucleus of the debate, and other things said about the issue tend to be complimentary or tangential. Along with scriptural sources and people’s experiences, a major topic that crops up is what scholars have had to say. What I’d like to put forward here about the view of scholars of the past is that many of them are not actually saying much of what’s claimed.

For example, some cite al-Qurtubi’s views on 2:275 which I covered in the post on the Qur’an, but as I highlighted (in the post on hadith), drawing on the sources holistically scholars concluded that jinn could penetrate the body to add potency to their whispers, not that the devil would penetrate the body to take it over and appropriate human autonomy. This is what Ibn Taymiyyah’s statement that “the leaders of Ahlussunnah agree that the jinns’ penetration of the human body is valid” was referring to in Majmu’ al-Fataawa, or Abul Hasan al-Ash’ari’s explanation (if we can soundly ascribe the Maqalaat to him) that “Ahlussunnah say that the jinn may penetrate the body of the afflicted.”

As for whether jinns take over a person’s limbs or intellect, then yes, Ibn Taymiyyah might have personally sympathised with this view but it’s one he noticeably doesn’t go on to ascribe to the leaders of Ahlussunnah instead reasoning it as an empirical fact (which I’ve asserted is incorrect in the ‘experiences’ post), saying: “it is something witnessed and felt for those who contemplate it.” The fact is, the view doesn’t seem to have been greatly held nor explicitly addressed in the way we do today. Yes, al-Qurtubi saw it as causing epilepsy, but think about it, even from al-Qurtubi’s point of view: causation is clearly not the same as taking over the body to pretend it has epilepsy! Many scholars of Ahlussunnah, past and present, have explicitly discussed the capabilities of devils, affirming from one perspective that their physical constitution allows them to be able to pass through a human body (and other things) but that their power (sultan) over humans is limited to waswasah (whispers). For clarity, there are two separate/distinct theological issues here:

1) that the faint physical constitution of jinns (like air) allows them to move through small crevices, including those within the human body;

2) that the power (sultan) jinns have is limited to waswasah/whispers, i.e. the power of suggestion (and not possession).

What has always surprised me, beyond how such matters have been conflated, is how people get away with an appeal to scholars that tends to rest on just a couple of names perceived to be in favour of possession. Although there are many scholars we're at liberty to cite, from whom we might infer a dismissal of the view, I’ll provide just a few here for some balance. I’ve chosen these luminaries because I believe that collectively they speak to the majority of British Sunni Muslims:

1. Ibn Hazm not only dismissed the idea of jinn possession explicitly, referring to it as a superstition (kharafaat), but held that “such things are not possible (i.e they don’t fall for it) except to the weak minds of the elderly…that he (the devil) can speak using someone’s tongue is senility and clear insanity; we seek protection in God from deception and affirming superstitions.”

2. Al-Tahawi’s commentary on previously cited hadiths in Mushkil al-Athaar resolutely puts it that the influence of the jinn on humans is limited to the power of suggestion through waswasah (whispers) saying, “The only thing people were commanded to do is seek protection from the devil against the power (sultan) he has over them which is waswasah (whispers) that incite an adoration for evil and a dislike of good…” Ibn al-Qayyim provides a similar commentary for the same hadith on cursing the devil in Zaad al-Ma’ad.

3. Al-Razi, the imam of kalam/Ash’arism/tafsir/fiqh/usul pretty much seems to suggest the same as al-Tahawi in his al-Tafsir al-Kabir, affirming that the physical constitution of jinns allows them to be able to pass through a human body (and other things) but that their power (sultan) over humans is whisperings. The latter point is seemingly further advocated where he explores two opinions that people hold on the devil’s touch suffered by the Prophet Job, with an emphasised exploration of the view that “the devil has absolutely no ability to confer diseases or painful afflictions.”

4. In more modern times, Ibn Ashur also holds to the Quranic narrative that limits the influence of the jinn to waswasah in Tahrir wa Tanwir, and in his explanation interprets the oft-cited hadiths consistently in that context.

In the same vein, there’s a final point that stoutly needs to be corrected about the Mu’tazilah, which also exposes the ignorance of those who engage in bad faith. As I wrote, those today who charge interlocutors with Mu'tazilism (in nearly every matter) know absolutely nothing about the scholarly tradition of the Mu'tazilah. On this matter, Qadi Abdul Jabbar, an imam of the Mu’tazilah, sympathised with Ahlussunnah’s view that jinns might be able to traverse a human body, stating that “if what we have argued about the faint constitution of the jinn and that their constitution is like air is correct, then it is not inconceivable that they may enter our bodies just as air or repeated breaths do.” Other Mu’tazilis didn’t even get to the point of dismissing possession per se since they erroneously believed that scriptural references to jinns were metaphorical and that jinns don’t exist in reality. What I’m highlighting here is that essentialising Mu’tazili opinion to deploy the fallacy of association (“this is just Mu’tazili!”) is plain ignorant. To add to this is the obvious point that not all of what the Mu’tazilis held was wrong - as if they got nothing right!

Whilst the aversion of early scholars towards the Mu’tazilah began as theological, the aversion quickly included legitimate political grievances towards them. This grievance was carried by later generations into a wider theological setting where misconceptualisations of many Mu’tazili views became essentialised and entrenched, with the group conveniently employed as theological bogeymen. Where some later medieval scholars would disparage the alleged views of the Mu’tazilah, it wasn’t always the case that the Mu’tazilah homogeneously held those views, if at all. In case someone misses the point here, I’m not launching a defence of the Mu’tazilah but highlighting how scholarship requires diligence when unpacking claims/assertions, let alone resorting to juvenile tactics.

Having said all this, I hope what I have presented in this series is clear and coherent. There are many British Muslims who do not really believe in possession (and other superstitions), but due to the militant way in which many advocates behave, most are intimidated into outward submission. If people want to believe in possessions then that's their (unhealthy) prerogative, but we'll not leave believers to be intimidated into accepting superstitions that are impediments to good health and faith, and opportunistically abused by pretenders.

May God guide us all to what is upright and beneficial for both abodes.

What to make of 'Jinn possession' claims. Part 4

When it comes to talking about whether jinn possession is real and a valid belief, often people will cite their experiences.

Here are some points to consider:

1. The purpose of theologians is to establish what God has told us. The theological validity of something is not established by what people feel or any other emotions. Claiming you've experienced something is of course your perogative, but we must recognise that it's not a theological argument, and has no evidentiary authority for claims about the unseen.

2. Experiences are a matter of perception, which is subjective. I'm not saying that people haven't experienced something but what they make of it is a matter of interpretation. It's logical that where a person has never been introduced to the notion of jinn possession, it's not an explanation s/he'd fall on - and as I've very briefly covered, the Islamic sources (nusus shar'iyyah) cannot be credibly taken that way. Many people claim things: some Hindus will claim they're touched by one (or more) of their gods, some Christians claim Jesus has spoken to them or that they've received the holy spirit. Some Muslims will visit shrines and claim to be literally "visited" by the dead saint buried there. And yes, tens of thousands (if not millions!) from each faith and tradition have made such claims, so based on claim and/or numbers, does that validate their interpretation of what they experienced? Of course not, and inherently their interpretation of an experience is shaped by their pre-conceived beliefs and ideas. A study (with limitations) offers some insight here. Now this is not to say that devils do absolutely nothing - as I've already stated (as so too have many other scholars past and present) the Qur'an explicitly refers to "touch" /المس - in the form of whispers (which everyone agrees on), but these whispers of a metaphysical nature do not in any way strip an individual of their autonomy. It's simply not in the remit of the devil (see 14:22).

3. It's an irresistible fact that only the people who believe in possession seem to experience it and interpret events in that way, just like only Hindus feel Shiva or Christians feel Jesus/holy spirit (and to argue that those who dismiss the idea also do but they don't know it is an incredibly weak assertion). One of the things the Hasanat saga reveals is that sincere souls were duped into believing that Hasanat was relieving them of the jinn that had supposedly possessed them. Think about it, as the result of Hasanat's so-called ruqyah, an agnostic non-Muslim who didn't even believe in what he was doing and really just putting on a show, many of his patients felt the jinn possessing them had been exorcised. Either we accept that it was all a scam that relied on a mistaken belief in possession, or we accept that non-Muslim exorcism (and/or ruqyah by a non-Muslim as a form of ibadah) is valid and works. If you assert that maybe they were mistaken in their belief that they were possessed, then how do we ascertain when a person is actually possessed as oppose to a misdiagnosis? If you assert that maybe the jinn didn't leave but pretended to, then what you're suggesting is that we should accept their claims that they were possessed, but we shouldn't accept their claims that they were relieved of that possession by a non-Muslim. You cannot have it both ways, and if you try to, then it's clear confirmation bias.

4. "But I witnessed the jinn, my friend/family (etc) spoke a language they didn't even know / spoke in a voice I didn't recognise!" Such phenomena have been widely documented amongst all types of people (usually following some trauma) including non-Muslims who dismiss the idea that the jinn actually exist. Foreign accent syndrome and polyglot aphasia are specific conditions that come to mind, but the explanation you opt for will rely a lot on your preconceived ideas - and as I've covered, the Islamic sources cannot be compellingly read as offering an explanation that rests on jinn possession.

5. In my anecdotal experience and having spoken to literally hundreds of people about their 'possession' experiences over the years, the way in which they describe what's happened always discloses how their preconceived ideas shaped their perception of the actual event. When I've probed into exactly what's occurred, it's been clear to see that the event could be taken a number of ways. What one learns pretty quickly in the realm of religious ministry is that for most people, religion doesn't run on reason but on emotion. People follow their instincts and backfill arguments to fit them.

Is Jinn possession established in the Sunnah? Part 3

Again, nowhere near.

Here I'll briefly deal with the most significant hadith cited in favour of possession. The aim is to make clear how the interpretation of particular hadith to establish that jinns take control of humans where the soul loses cognitive and physical autonomy is either a misunderstanding of the hadith, exceedingly far-fetched and weak, and in some cases relies on ambiguous wording - all of which is an illegitimate way to establish what is meant to be a theological imperative. As I've stated, I'm not dealing with the entirety of the subject but the popular arguments made for possession.

Here are some of the most cited hadith used for jinn possession, with very brief comments:

1. Hadith of Ibn Abbas (al-Bukhari and Muslim) about a women suffering from seizures who came to the Prophet and said: "I suffer from seizures and I become exposed, so call on God for me." The Prophet replied: 'If you want, you can be patient and you'll have paradise, or if you want I can call on God to cure you." She responded: "I'll have patience...but call on God that I do not become exposed." The discussion on possession arises because in another narration she blames the devil for her exposure. Yet in that narration she does not ascribe the seizures to the devil and neither does the Prophet. Furthermore, we almost certainly know that the Prophet didn't view the seizures as the works of the devil for it is inconceivable that a believer would come to the Prophet complaining about the devil whom the Prophet could effortlessly ward off, yet would consciously allow the devil to persist and instead tell the believer to have patience with him, not even encouraging her to take refuge in God as per his advice to others (in keeping with 41:36). This is an important hadith as it explicitly relates how the Prophet saw a seizure, clearly he viewed it as a physiological problem which God poses to test human patience and godly resolve (indicated by his response in the story). Not only is it far-fetched to interpret this hadith as evidence of jinn possession, it's counter-productive as it establishes the opposite!

2. Hadith of Uthman b. Aas al-Thaqafi (Sahih Muslim) whom the Prophet told to lead his people in prayer. He responded "I find something within me." The Prophet placed his hand on his chest and back and then said: "Lead your people in prayer, and the one who does so should lighten it for amongst them are the old, the sick..." What he felt within him, as al-Nawawi points out in his commentary of Sahih Muslim, is the whisperings of the devil that sought to confuse him. This is made evident by the other narration in al-Bukhari and Muslim, where he says to the Prophet: "The devil comes between me and my recitation, confusing me." The Prophet responded: "That is the devil Khanzab. So if you feel him (trying to confuse you), seek refuge in God from him..." With what is consistent with waswasah, the Prophet instructed him to seek refuge in God, acting on the verse: "If Satan should prompt you to do something, seek refuge with God." (7:200, 41:36) It is extremely unsound to interpret the event as Uthman being possessed by the devil. (The narration in Ibn Majah is problematic as it contradicts narrations far more sound than it, and its various chains include weak narrators or those known for munkar narrations.)

3. Hadith of Safiyyah b. Huyay (al-Bukhari and Muslim), the noble wife of the Prophet, who visited the Prophet whilst he was in I'tikaf. The Prophet said to two Companions who noticed him walking her home later that night and feared that they may misunderstand the affair: "The devil runs in the veins of Adam, and I feared that he would plant something in your hearts." Some scholars took the statement concerning the devil running through the veins of Adam literally, others took it figuratively. I think the context strongly suggests that "the devil runs in the veins of Adam" was meant as a figuritive expression. However, the key point here is that the Prophet doesn't say that he fears the devil will possess them, but clearly refers to the devil's planting of ill-thoughts in their hearts - waswasah.

A very important point to note is that it was mainly this hadith led scholars to conclude that the devil can enter the body - NOT to possess the human but simply to get closer to the heart/brain where the devil's whispers would be even more potent. This was the position of scholars who advocated that the devil could penetrate the body (i.e. to have more potency), not that the devil would penetrate the body to take over and appropriate human autonomy. Those who advocate possession and draw on classical scholars completely misunderstand what the vast majority of those scholars were actually saying!

4. Hadith of Ya'la b. Murrah (Musnad Ahmad and others) about a young boy who had seemingly been afflicted with insanity. The Prophet said to him: "Get out enemy of God, I am the Prophet of God!" The particular narration often cited in Musnad Ahmad is weak having a broken chain (munqati') although there are numerous corroborating narrations, the acceptability of which have been debated by muhaddithin, some of whom have deemed them reliable. Even if we were to accept the narration, it does not tell us that the boy was possessed, nor does it clarify what the Prophet was referring to. He may have been speaking to the affliction itself, or conceivably, speaking to a devil hiding within the boy to get closer to the heart/brain where the devil's whispers would be even more potent (as explained in point 3). Also note that the Prophet didn't perform ruqyah for possession as has become the habit today, but commanded departure - and of exactly what he intended, we cannot be certain. (In a hadith of Ibn Abbas, agreed to be a fiction by all muhaddithin, a mouse jumped out of the boy's mouth!) Asserting this inconclusive narration as the basis for substantiating a theological imperative is simply absurd by any standard of religious reasoning and theology construction, especially when the interpretation contradicts the Quranic narrative.

The next post addresses what we're to make of people's experiences.

Is Jinn possession established in the Qur'an? Part 2

Nowhere near.

Here I'll briefly deal with the most significant verse cited in favour of possession (2:275). The aim is to make clear how the interpretation of verses that try to establish that jinns take control of humans where the soul loses cognitive and physical autonomy is exceedingly far-fetched and weak, and misunderstands what's been said by scholars of the past. I'm not dealing with the entirety of the subject but the popular arguments made for possession.

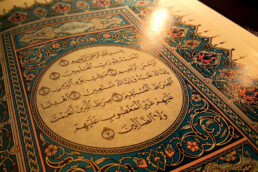

The MOST cited Quranic evidence for jinn possession, and the strongest according to its advocates, is the following verse:

But those who consume usury will rise up like someone tormented/driven insane by the devil’s touch.

Qur'an 2:275

This verse refers to the resurrection of those who practice usury, who shall come back to life behaving like someone who is insane. al-Qurtubi explains this behaviour as caused by the usury weighing heavily down on their stomachs (from its consumption) which causes the usurer to continously lose balance and fall over thus resembling someone crazy. The verse led scholars to explore the nature of the statement that God made in 2:275: was it literal or figuritive? If it's literal, can a devil merely touch someone to cause epilepsy? Given that the verse is related to the afterlife, and if it's taken literally, does it only refer to interactions between humans and devils in the afterlife? On all of these al-Qurtubi records the variant views. But what the scholars were NOT discussing was whether jinns take control of humans personally.

Explaining the devil's "touch"

1. The verse clearly refers to touch, NOT autonomy-losing possession. In a desperate bid to make the verse about possession, some draw on al-Qurtubi's 11-12th points of commentary (on 2:275) where he discusses how the touch of the devil can afflict a person. To be clear: al-Qurtubi is often misrepresented here - he doesn't say jinns take control of humans where the soul loses cognitive and physical autonomy. He claims that the touch causes a seizure, going on to define "touch" as the cause of insanity (junun) and NOT a jinn inside of a human pretending to be insane. al-Qurtubi then goes on to express two contentions:

a) with those who dismiss epilesy as being caused by the jinn, claiming that epilepsy is a physiological phenomenon (and not a supernatural one), and;

b) with those that claim the devil cannot traverse the human body, and that no such "touch" ever occurs.

Now the idea that epilepsy is simply a supernatural phenomenon is one nobody legitimately accepts today. However I sympathise with his second contention (which I'll explain in a later post).

2. Some draw on Ibn Taymiyyah's claim to consensus, somthing I'll deal with later on. However, according to Ibn Taymiyyah's (et al) interpretational principles, the strongest form of tafsir is to understand the Qur'an by means of the Qur'an itself (تفسير القران بالقران), i.e. an inter-textual analysis. So in this vein, if we look at God's use of the "devil's touch" elsewhere in the Qur'an, what might we strongly conclude? That "touch" refers to the whispers (waswasah) of the devil. Being touched by devils is to be subjected to their whispers (i.e figuratively touched by them) which either incite you to disobedience or misguidance, or draw on vulnerable emotions to push you over the edge.

3. For an inter-textual analysis: the most significant and detailed verses on the devil's touch are:

Those who are aware of God think of Him when the touch of Satan prompts them to do something and immediately they can see [straight]; the followers of devils are led relentlessly into error by them and cannot stop.

Qur'an 7:202-204

The verses simply tell us that God-conscious people think of God and seek refuge in him when the touch of Satan prompts them to do something. Here God relates the devil's touch as being his misguidance - by remembering God and seeking refuge in Him, they overcome a touch that leads others (followers of devils, or literally "their brothers") who don't remember God into error (الغي). Interestingly, al-Qurtubi doesn't repeat his contentions here, and considering views variant to his own without disparagement, cites Abu Ja'far al-Nuhas who said that "touch" refers to the devil's whispers. Understanding the "devil's touch" in the Quranic context is really that simple.

4. But to briefly add to this, another notable reference to "devil's touch" concerns the Prophet Job who cried out to his Lord: "Satan has touched me with weariness and suffering.’" (38:41) This verse creates a double-edged dilemma for advocates of possession. If they use it literally it helps in the argument that the devil can cause physical suffering, but taking it literally also means that it's through touch and NOT possession. Even if they had found a way around this dilemma (which they haven't), would they have the temerity to suggest that the Prophet of God Job was possessed, and thus open to be inspired, by the devil?! If the devil had such power, especially over Prophets, it'd be the end of truth and monotheism!

So what did Job actually say?

The Arabic phrase can be taken in a number of ways depending on the 'ba' (preposition). Grammatically, we may take it as the devil's touch causing Job's suffering, OR it can be taken as the devil's waswasah which exploited Job's suffering and vulnerability in an attempt to misguide him. For many reasons, it seems that the most reasonable and consistent way (inter-textually) to take his statement is that the devil would whisper to him using his vulnerabilities to incite him against God. To provide a couple:

- The context of Job's story: the devil believed he could misguide Job and turn him away from God. Throughout the Qur'an the term "touch" can be consistently understood as waswasah, which the Quran tells us is through "whispers into the hearts of people" (114:4) with "no power over you except to call you." (14:22) Notably, it's related (in the Isra'iliyaat and by Muslim historians) that the devil appeared to Job as an old man suggesting that God was ignoring his supplications and prayers.

- With what is consistent with waswasah, Job's reaction (as 38:41 illustrates) was to seek refuge in God. Thus he acted as God expects: "If Satan should prompt you to do something, seek refuge with God." (7:200, 41:36)

[Note: some exegetes merely considered it godly etiquette that Job ascribed the harm to the devil since it is inappropriate to ascribe negative things to God.]

Now as I've said, this is a very short treatment of the most significant verse cited in favour of possession. This isn't even being 'scholarly' yet and I'm sure much of this is apparent for most laymen who actually engage the Qur'an. There's so much more that can be explained, and many more verses that we can draw on, but for the purposes of a short post I hope that this very short treatment suffices.

The next post looks at some of the most significant hadith cited in favour of possession.